Why you need to learn async in .NET

I had an opportunity to teach a quick class yesterday about what’s new in .NET 4.0. One of the topics was the TPL (Task Parallel Library) and how it can make async programming easier. I also stressed that this is the direction Microsoft is going with for C# 5.0 and learning the TPL will greatly benefit their understanding of the new async stuff. We had a little time left over and I was able to show some code that uses the Async CTP to accomplish some stuff, but it wasn’t a simple demo that you could jump in to and understand so I thought I’d thrown one together and put it in a blog post.

The entire solution file with all of the sample projects is located here.

A Simple Example

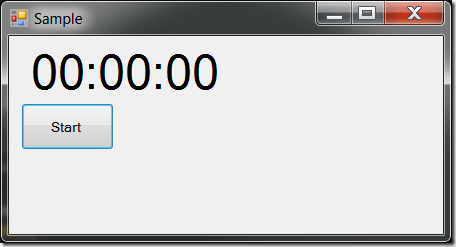

Let’s start with a super-simple example (WindowsApplication01 in the solution). I’ve got a form that displays a label and a button. When the user clicks the button, I want to start displaying the current time for 15 seconds and then stop. What I’d like to write is this:

lblTime.ForeColor = Color.Red;

for (var x = 0; x < 15; x++)

{

lblTime.Text = DateTime.Now.ToString("HH:mm:ss");

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

lblTime.ForeColor = SystemColors.ControlText;

(Note that I also changed the label’s color while counting – not quite an ILM-level effect, but it adds something to the demo!)

As I’m sure most of my readers are aware, you can’t write WinForms code this way. WinForms apps, by default, only have one thread running and it’s main job is to process messages from the windows message pump (for a more thorough explanation, see my Visual Studio Magazine article on multithreading in WinForms). If you put a Thread.Sleep in the middle of that code, your UI will be locked up and unresponsive for those 15 seconds. Not a good UX and something that needs to be fixed. Sure, I could throw an “Application.DoEvents()” in there, but that’s hacky.

The Windows Timer

Then I think, “I can solve that. I’ll use the Windows Timer to handle the timing in the background and simply notify me when the time has changed”. Let’s see how I could accomplish this with a Windows timer (WindowsApplication02 in the solution):

public partial class Form1 : Form

{

private readonly Timer clockTimer;

private int counter;

public Form1()

{

InitializeComponent();

clockTimer = new Timer {Interval = 1000};

clockTimer.Tick += UpdateLabel;

}

private void UpdateLabel(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblTime.Text = DateTime.Now.ToString("HH:mm:ss");

counter++;

if (counter == 15)

{

clockTimer.Enabled = false;

lblTime.ForeColor = SystemColors.ControlText;

}

}

private void cmdStart_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblTime.ForeColor = Color.Red;

counter = 0;

clockTimer.Start();

}

}

Holy cow – things got pretty complicated here. I use the timer to fire off a Tick event every second. Inside there, I can update the label. Granted, I can’t use a simple for/loop and have to maintain a global counter for the number of iterations. And my “end” code (when the loop is finished) is now buried inside the bottom of the Tick event (inside an “if” statement). I do, however, get a responsive application that doesn’t hang or stop repainting while the 15 seconds are ticking away.

But doesn’t .NET have something that makes background processing easier?

The BackgroundWorker

Next I try .NET’s BackgroundWorker component – it’s specifically designed to do processing in a background thread (leaving the UI thread free to process the windows message pump) and allows updates to be performed on the main UI thread (WindowsApplication03 in the solution):

public partial class Form1 : Form

{

private readonly BackgroundWorker worker;

public Form1()

{

InitializeComponent();

worker = new BackgroundWorker {WorkerReportsProgress = true};

worker.DoWork += StartUpdating;

worker.ProgressChanged += UpdateLabel;

worker.RunWorkerCompleted += ResetLabelColor;

}

private void StartUpdating(object sender, DoWorkEventArgs e)

{

var workerObject = (BackgroundWorker) sender;

for (int x = 0; x < 15; x++)

{

workerObject.ReportProgress(0);

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

}

private void UpdateLabel(object sender, ProgressChangedEventArgs e)

{

lblTime.Text = DateTime.Now.ToString("HH:mm:ss");

}

private void ResetLabelColor(object sender, RunWorkerCompletedEventArgs e)

{

lblTime.ForeColor = SystemColors.ControlText;

}

private void cmdStart_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblTime.ForeColor = Color.Red;

worker.RunWorkerAsync();

}

}

Well, this got a little better (I think). At least I now have my simple for/next loop back. Unfortunately, I’m still dealing with event handlers spread throughout my code to co-ordinate all of this stuff in the right order.

Time to look into the future.

The async way

Using the Async CTP, I can go back to much simpler code (WindowsApplication04 in the solution):

private async void cmdStart_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblTime.ForeColor = Color.Red;

for (var x = 0; x < 15; x++)

{

lblTime.Text = DateTime.Now.ToString("HH:mm:ss");

await TaskEx.Delay(1000);

}

lblTime.ForeColor = SystemColors.ControlText;

}

This code will run just like the Timer or BackgroundWorker versions – fully responsive during the updates – yet is way easier to implement. In fact, it’s almost a line-for-line copy of the original version of this code. All of the async plumbing is handled by the compiler and the framework. My code goes back to representing the “what” of what I want to do, not the “how”.

I urge you to download the Async CTP. All you need is .NET 4.0 and Visual Studio 2010 sp1 – no need to set up a virtual machine with the VS2011 beta (unless, of course, you want to dive right in to the C# 5.0 stuff!). Starting playing around with this today and see how much easier it will be in the future to write async-enabled applications.